Introduction to Bioprocessing¶

Imagine you're making bread. You mix flour, water and yeast and then you let the dough rise. The yeast eats sugars and produces gas, which makes the dough grow. Bread, cheese, wine and beer are the first bioprocessed products that humanity discovered: in all these cases, living organisms like yeast or bacteria carry out natural processes such as fermentation in order to transform a product into something else.

The concept at the base of modern bioprocessing is very similar. Instead of making bread, scientists use living cells (like bacteria, yeast or animal cells) to make useful products such as medicines, vaccines or enzymes. The process usually happens in large tanks called bioreactors.

This was the case of Novavax COVID-19, a vaccine produced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Such vaccine was based on protein subunits: the final product contained nanoparticles carrying a small concentration of spike protein and an adjuvant matrix, capable of stimulating the human immune system. The idea at the base of this vaccine was to stimulate the production of antibodies in humans for COVID-19 Spike protein. Attacking Spike proteins means making viral entry very difficult, since they interact with the host cell receptors.

Novavax's COVID-19 vaccine was made by using insect cells as factories to produce the virus's Spike protein. Scientists inserted the genetic instructions for the Spike into a baculovirus, which is then used to infect the cells inside bioreactors. The "infected" cells produced a large amount of Spike protein, which is finally purified and used in the final product.

The COVID-19 Spike protein was sequenced rapidly in early 2020: in other words, from that moment it became possible to chemically design it in a vial. Why, then, did companies choose to rely on bioreactors?

The immediate and simplest answer is for quantitative reasons: there was a massive demand for vaccines during the pandemic. Bioreactors can work in a continuous and highly monitored environment, which guarantees optimized operational conditions and thus higher production. As a consequence, the second answer can be for safety reasons: these operations can be easily conducted in sterilized environments, under specific pharmaceutical standards. This helps, for example, improve the stability of the protein during the whole production process, avoiding excessive immune response and side effects in patients. In the end, there is also a third reason, which is purely biological. This is how the COVID-19 Spike protein looks like:

(from Alexandra C. Walls, Young-Jun Park, David Veesler Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein reveals the architecture of the key player of viral entry into host cells)

Such protein is far from being a small, simple and linear chain of amino acids. It contains more than one thousand residues and its three-dimensional architecture depends on numerous post-translational modifications. Even small alterations in certain regions may result in a non-functional protein, rendering the vaccine ineffective.

Cellular bioprocessing is generally complex and time-consuming, but it remained essential for a specific reason: only cells provide the enzymatic machinery needed to fold, glycosylate and stabilize complex proteins in a way that is fully compatible with biological systems.

What is a bioreactor and how does it work¶

As we have already seen, in bioprocessing many different biological products can be obtained. Each product relies on specific cellular reactions and growth conditions: some processes may benefit from variable flow rate to follow the dynamics of cell growth, while others require a constant input of nutrients to keep the reaction stable over time. For this reason, not all the bioreactors are designed in the same way.

This is the scheme of a typical bioreactor.

In this picture it is possible to recognize several key components:

- The tank, where the cells and the media are located

- The sensors, to monitor all the important parameters, such as temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, cell density etc.

- The controllers (often automated), that adjust input parameters based on sensor feedback

- Ports and tubing, for adding nutrients or removing samples

The bioreactor shown in the picture is called Continuous Stirred-tank bioreactor or simply CSTR. It has a built-in mechanical stirrer to mix the culture and make sure nutrients and oxygen are evenly distributed. This is the bioreactor typically used for antibiotic production, especially in the presence of cells insensible to shear stress, like bacteria and fungi.

How does a CSTR reactor work? 🎥 Watch: CSTR Reactor Operation (YouTube) - See the mixing and operation starting from minute 0:53

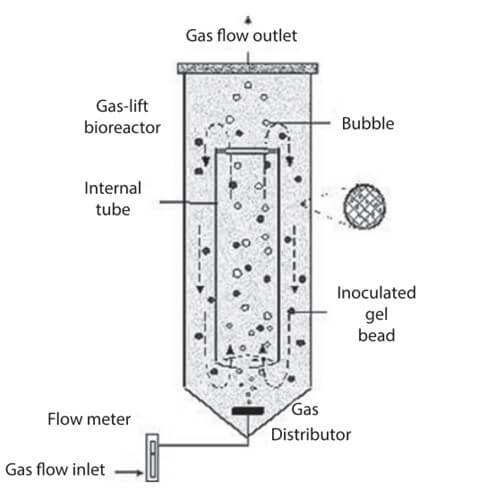

For more delicate cells, like the animal cells, the most used bioreactor is the Airlift (or loop-air) bioreactor.

Figure: Airlift fermentor. Image Source: Kuila, A., & Sharma, V. (2018). Principles and applications of fermentation technology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Figure: Airlift fermentor. Image Source: Kuila, A., & Sharma, V. (2018). Principles and applications of fermentation technology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

How does an Airlift bioreactor work? 🎥 Watch: Airlift Bioreactor Operation (YouTube Shorts) - Observe how air bubbles drive the circulation

The main difference between an Airlift bioreactor and a CSTR is in the strategy adopted for stirring the culture to reduce the shear stress. In the Airlift, the air is insufflated at the bottom of the reactor. The density of the culture is decreased due to the formation of bubbles (the density of the air is lower than the density of the water), which move to the top. At the top of the reactor, the bubbles burst: in that part of the reactor, the culture density gets lower and goes down again.

Another option is the fixed-bed or packed-bed bioreactor.

!

Figure: Packed bed fermentor. Image Source: Kuila, A., & Sharma, V. (2018). Principles and applications of fermentation technology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

In this case the cells are immobilized on a solid support, like fibers or spheres, while the medium with nutrients flows inside the bed. This bioreactor is generally used for water purification and slower processes, because it allows for very long operations (without waste of biomass!) at high cellular density. It is not highly recommended for aerobic processes since the oxygen transfer within the cells and the medium is not particularly enhanced, due to the presence of the solid support (which decreases the surface area of exchange between the two interfaces) but also to the formation of biomass biofilm (the oxygen coming from the medium has to diffuse through the width of the layer to reach the cells located near the solid support).

How does a packed bed bioreactor look and work? 🎥 Watch: Packed Bed Bioreactor Operation (YouTube Shorts) - See how medium flows through the immobilized biomass

How to model a bioreactor¶

Today's problem session will be based on modeling a CSTR. To do this, it is fundamental to learn how to quantitatively describe the phenomena occurring within the system by formulating mass, energy and momentum balances.

The first step is to identify the system, the surrounding and the boundary. The system is the part of the process we are focusing on. For a CSTR, the system is the liquid inside the tank where the reaction happens, including any microorganisms, substrates and products.

The surrounding is everything outside the system that can interact with it. In the case of the CSTR, for instance, this could be the air around the tank, the room, the pipes leading to and from the tank and any cooling/heating fluid.

Finally, the boundary is the surface that separates the system from the surroundings. In a CSTR we can consider the tank walls, inlet and outlet pipes as boundaries. The boundaries can allow mass (reactants in, products out), energy (heating/cooling) or momentum (mixing) to cross it.

The interaction between system and surroundings is typically by one or more of the following mechanisms:

- A flowing stream

- A stress (a contact force on the boundary, usually normal or tangential to it)

- A body force, like gravity

- Work, as the electrical energy coming from a motor

All balance equations follow the same fundamental principle: Rate of accumulation = Rate of input - Rate of output + Rate of generation - Rate of consumption

Or mathematically:

$$\frac{d(\text{quantity in system})}{dt} = \text{In} - \text{Out} + \text{Generation} - \text{Consumption}$$

This is essentially accounting: we track what comes in, what goes out, what's created, and what's destroyed.

The mass balance¶

Total Mass Balance¶

For the entire liquid volume in the reactor:

$$\frac{dM}{dt} = \dot{m}_{in} - \dot{m}_{out}$$

Where:

- $M$ = total mass in the reactor (kg)

- $\dot{m}_{in}$ = mass flow rate entering (kg/s)

- $\dot{m}_{out}$ = mass flow rate leaving (kg/s)

What does this mean? If more mass enters than leaves, the mass in the reactor increases. If we're at steady state (constant volume), then $\frac{dM}{dt} = 0$, so $\dot{m}_{in} = \dot{m}_{out}$.

Component Mass Balance¶

For a specific component (like glucose, a substrate, or biomass):

$$V\frac{dC_i}{dt} = F_{in}C_{i,in} - F_{out}C_i + r_iV$$

Where:

- $V$ = reactor volume (L or m³)

- $C_i$ = concentration of component $i$ (g/L or mol/L)

- $F_{in}$, $F_{out}$ = volumetric flow rates in and out (L/s)

- $C_{i,in}$ = inlet concentration of component $i$

- $r_i$ = reaction rate (production or consumption rate per unit volume)

What does this mean? This tracks a specific substance. The term $r_iV$, that we have already seen in the previous lectures, is crucial for bioreactors:

- If $r_i > 0$: the substance is being produced (like biomass growing or a product forming)

- If $r_i < 0$: the substance is being consumed (like glucose being eaten by bacteria)

Example: For biomass (X) growing with specific growth rate $\mu$:

$$V\frac{dX}{dt} = F_{in}X_{in} - F_{out}X + \mu XV$$

The term $\mu XV$ represents cell growth - cells making more cells!

The energy balance¶

The energy balance tracks heat and work:

$$\frac{dU}{dt} = \dot{Q} - \dot{W} + \sum_{in}\dot{m}_{in}H_{in} - \sum_{out}\dot{m}_{out}H_{out}$$

For most bioreactors, we simplify this to:

$$\rho V C_p\frac{dT}{dt} = \dot{Q} + (-\Delta H_r)r V + \dot{m}_{in}C_p(T_{in} - T) - \dot{m}_{out}C_p(T - T_{ref})$$

Or even simpler for constant flow and density:

$$\rho V C_p\frac{dT}{dt} = \dot{Q} + (-\Delta H_r)r V + \rho F_{in}C_p(T_{in} - T)$$

Where:

- $T$ = reactor temperature (K or °C)

- $\rho$ = density (kg/m³)

- $C_p$ = heat capacity (J/kg·K)

- $\dot{Q}$ = heat transfer rate (W) - positive if heating, negative if cooling

- $\Delta H_r$ = heat of reaction (J/mol or J/kg)

- $r$ = reaction rate

What does this mean?

- Left side: How fast the temperature changes

- First term on right ($\dot{Q}$): Heat added by cooling jacket or heater

- Second term ($(-\Delta H_r)rV$): Heat produced or consumed by the biological reaction. Many fermentations are exothermic (they release heat), so in that case, this term is positive and can heat up the reactor

- Third term: Heat brought in by the incoming stream

Practical insight: Microbial growth releases heat, and a large-scale fermentation can get very hot without cooling. That's why industrial bioreactors generally have cooling jackets.

3. The momentum balance¶

The momentum balance is less commonly needed for basic bioreactor modeling, but it's important for understanding mixing and flow:

$$\frac{d(M\vec{v})}{dt} = \sum \vec{F}$$

Where:

- $M\vec{v}$ = momentum (mass × velocity)

- $\vec{F}$ = forces acting on the system

For a well-mixed CSTR, we often assume perfect mixing (as in the problem session!), so we don't need detailed momentum balances. However, the momentum balance tells us:

- How much power the stirrer needs to provide

- Whether mixing is sufficient for uniform conditions

- How fluids flow through the reactor

Practical consideration: The stirrer does work on the fluid, which also adds heat! In large bioreactors, stirring can contribute significantly to heating.

Simplifications for a Typical CSTR¶

For a well-mixed CSTR at steady state with constant volume:

Mass balance for substrate (S): $$0 = F(S_{in} - S) - \frac{\mu X S}{Y_{X/S}(K_s + S)}V$$

Mass balance for biomass (X): $$0 = F(X_{in} - X) + \mu X V$$

Energy balance (if needed): $$0 = \dot{Q} + (-\Delta H_r)r V + \rho F C_p(T_{in} - T)$$

Where $Y_{X/S}$ is the yield coefficient (how much biomass per substrate) and $K_s$ is the half-saturation constant (Monod kinetics)

Bioprocessing: is it always a good idea?¶

At the start of the lecture we discussed about the product of Novavax COVID-19 by using insect cells. In that case, due to the complex nature of the Spike protein, bioprocessing seems to be the most convenient choice to guarantee compatible (safe!) products. Is this always true?

In general, bioprocessing is presented as an alternative to the chemical synthetic production approach. In chemical synthesis, products are created through controlled chemical reactions between non-living materials. This approach is often faster, easier to scale and well-suited for producing small, simple molecules such as solvents, plastics or basic drugs.

The production of Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) is a good example of chemical synthesis. Chemists start with simple raw materials such as glucose. Through a series of controlled chemical reactions, they change the structure of glucose step by step to obtain Vitamin C. This pathway is well known under the name of Process Reichstein.

Source: R. Wohlgemuth, "Interfacing biocatalysis and organic synthesis", 2007

These reactions usually require strong acids or bases, high temperatures, and catalysts to make the process fast and efficient. After the reaction, the mixture contains impurities, so the final Vitamin C must be purified through filtration and crystallization. This process is fast, can be scaled easily, and works well for small and stable molecules, but it generates chemical waste and uses non-renewable materials. This creates the need of finding a more sustainable alternative, relying on bioprocessing.

Recent advances in biotechnology have made it possible to develop fully biological processes using genetically engineered microorganisms such as Ketogulonicigenium vulgare and Erwinia herbicola. These microbes can carry out all the necessary reactions inside a bioreactor, converting glucose directly into vitamin C or its key intermediate, 2-keto-L-gulonic acid. Compared to traditional chemical synthesis, this bioprocessing approach is more sustainable, requires milder conditions, and generates less waste, making it a promising alternative for environmentally friendly vitamin C production. Then, why are companies still using the Reichstein process to produce Vitamin C?

In industrial production, the chemical synthesis is still dominant, since it offers higher yields and productivity compared to fully biological methods. In the traditional chemical route, starting from glucose, factories can achieve a yield of around 90–95% — meaning that almost all of the starting material is efficiently converted into the desired product, ascorbic acid. The process is also fast, often completed within a few days.

In contrast, bioprocessing methods that rely entirely on microorganisms (such as Ketogulonicigenium vulgare) usually reach yields around 60–75%, depending on the strain and fermentation conditions. The process can take several days to over a week, since cells grow and produce the product gradually.

This lower yield and longer processing time make bioprocessing less efficient and more expensive at large industrial scale. Which are the ways to improve Bioprocessing accuracy?

How to improve bioprocessing yield?¶

Different strategies can be adopted for improving the quality of bioprocesses.

It is essential to maintain tight control of critical parameters such as pH, dissolved oxygen, and nutrient concentrations. Using inline sensors and continuous monitoring technologies ensures that cell conditions remain optimal throughout the process.

Adopting advanced feeding strategies and operational modes — for example, fed-batch or perfusion — and optimizing the growth medium can increase yields, reduce batch-to-batch variability, and improve consistency.

Digitalization and automation of bioprocesses, including data collection and analysis, help minimize human error, increase operational efficiency, and support Quality by Design (QbD) principles

Together, these approaches make bioprocesses more robust, reproducible, and compliant, ultimately improving the quality of the final product.

Sources:

- Keech C, Albert G, Cho I, Robertson A, Reed P, Neal S, Plested JS, Zhu M, Cloney-Clark S, Zhou H, Smith G, Patel N, Frieman MB, Haupt RE, Logue J, McGrath M, Weston S, Piedra PA, Desai C, Callahan K, Lewis M, Price-Abbott P, Formica N, Shinde V, Fries L, Lickliter JD, Griffin P, Wilkinson B, Glenn GM. Phase 1-2 Trial of a SARS-CoV-2 Recombinant Spike Protein Nanoparticle Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020 Dec 10;383(24):2320-2332. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2026920. Epub 2020 Sep 2. PMID: 32877576; PMCID: PMC7494251.

- Montastruc JL, Biron P, Sommet A. NVX-Cov2373 Novavax Covid-19 vaccine: A further analysis of its efficacy using multiple modes of expression. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2022 Dec;36(6):1125-1127. doi: 10.1111/fcp.12794. Epub 2022 May 7. PMID: 35502459; PMCID: PMC9348229.

- Levenspiel, O. (1999). Chemical reaction engineering (3rd ed.). Wiley.

- Zou W, Liu L, Chen J. Structure, mechanism and regulation of an artificial microbial ecosystem for vitamin C production. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2013 Aug;39(3):247-55. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2012.706250. Epub 2012 Sep 21. PMID: 22994289.